The Dark Times

One day in late October, a neighbor boy on the block where we lived years ago observed that we were beginning “the dark times.” It seems to amuse Craig to recall this comment each fall around this time. It’s an apt observation, considering the decreasing daylight hours, the encroaching return to Standard Time, and the way our evening rituals have been shifting for the last several weeks.

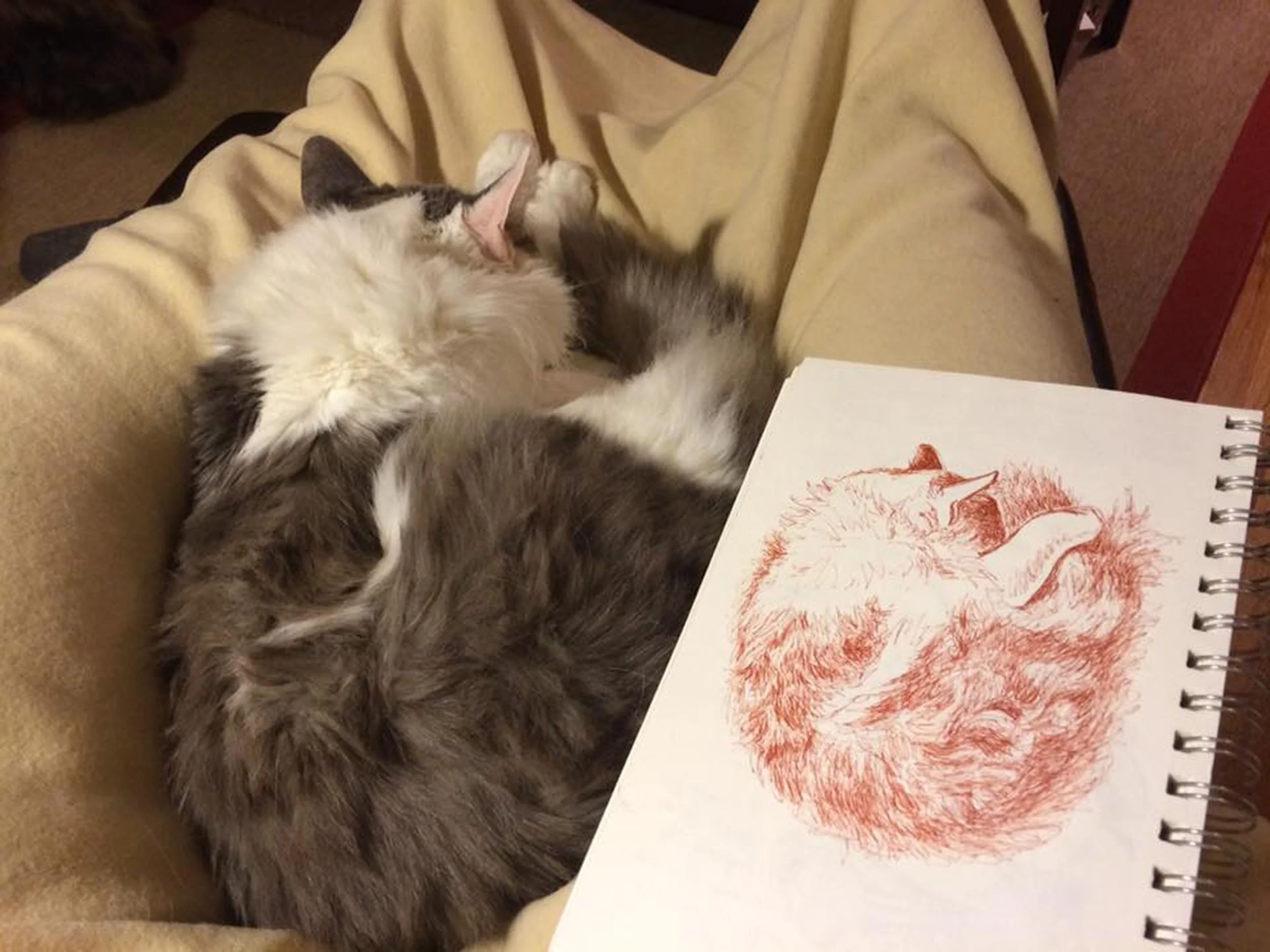

I couldn’t tell you exactly when we last went outside after dinner, whether to pull a few weeds or just sit on the patio and savor the lingering twilight; the seasonal shift in our habits has been discreet and gradual. Now we turn on the lamps, brew a mug of herbal tea, and settle in our favorite chairs with a book or magazine, our laps usually warmed by a snoozing cat.

Here in Minnesota, we tend to see September as the beginning of fall, with the state fair, which ends on Labor Day, as the last blast of summer. I recall that, when I was a child, school always started after that—never in August, surely.

One clear herald of fall was the voice of Ray Christensen coming over the radio in our kitchen, announcing Minnesota Golden Gophers college football games; it signaled the welcome seasonal shift and the imminence of my September birthday. Even the team colors, maroon and gold, looked like fall. I didn’t actually care one whit for football, but I relished the arrival of cooler, drier air and everything associated with it, including football on the radio, and school. (I can almost smell sharpened pencils and hear the crackle of newly opened schoolbooks.) I also tended to find my mother’s cheerful support for her alma mater kind of contagious, despite my lack of interest in the game itself.

September 1 is the beginning of meteorological fall, based on monthly average temperatures—average being the key word here. Much of September often feels an awful lot like summer, at least until after the autumnal equinox, which marks the beginning of astronomical fall.

The equinox on September 22 arrives amid a spell of rapidly diminishing daylight—the shrinking time span between dawn and dusk is quite noticeable, as is the sun’s march southward. This change in position of our star slows as we approach the solstice, giving the impression that it stops changing at all for about a week before and after that event, hence the Latin word solstitium, “point at which the sun seems to stand still.”

To my Celtic and Anglo-Saxon ancestors, the equinoxes more or less divided the year into two seasons, summer and winter. They weren’t terribly precise about it, however, perhaps because Anglo-Saxons based their months on moon phases, beginning with each new moon, (The Venerable Bede, writing in the early 8th century, called this the “lunar light,” assumed to mean the first sighting of the new crescent.) This year, the new moon following the fall equinox became visible by October 23, marking the beginning of Wintermonath, or “Winter Month”—if we were still using the Anglo-Saxon calendar.

I don’t know what the Celts called their months, or if they even had months. They divided the year into eight segments: the quarter days (equinoxes and solstices) and the cross-quarter days (halfway between those points). But I do know that they called the holiday we know as Halloween, which is a cross-quarter day, Samhain (prounounced sau-un), meaning “summer’s end”—which was also their New Year. Samhain actually fell on what is now November 1, but, just as we do today, they celebrated the festival on its eve. They did so because a day was considered to begin at sunset.

The Celtic cross-quarter days, which, besides Samhain, include Imbolc (Feb. 1), Beltane (May 1), and Lughnasadh (Aug. 1), were “fire festivals”—occasions for bonfires, considered helpful in warding off malevolent spirits that liked to roam at night. This was especially true during winter, beginning with nightfall on Samhain — when the dark of night is clearly longer than the daylight — and continuing until the eve of May Day, when daylight overwhelms the night again. I don’t know why Aug. 1 would also be a fire festival; maybe it was simply to maintain the symmetry of the “Wheel of the Year.”

But it was imperative at Samhain, when the “veil” or “fog” separating the world of mortals from the world of the fairy folk and spirits was lifted or thinned or full of holes, depending on which metaphor you prefer. At least at night. Not that fairies and elves and spirits were necessarily evil; they were more like apex predators—that is, dangerous. And they held grudges. And you could never be sure you hadn’t offended one at some point during the year.

That veil didn’t fall back into place right after Samhain, either; it was absent all winter. So as people stayed indoors by the fireplace and engaged in useful handcrafts like knitting, they told each other scary stories about supernatural beings and the ways in which regular people managed to outwit them—or not. Even on Christmas eve it was a tradition to tell ghost stories, a custom that Charles Dickens tapped into with his iconic “A Christmas Carol.”

After the holiday, when the squirrels feast on the erstwhile jack-o-lanterns, and I retreat indoors.

For me, I’d rather turn up the thermostat, put my feet up, and read a story, preferably one that’s not too scary.